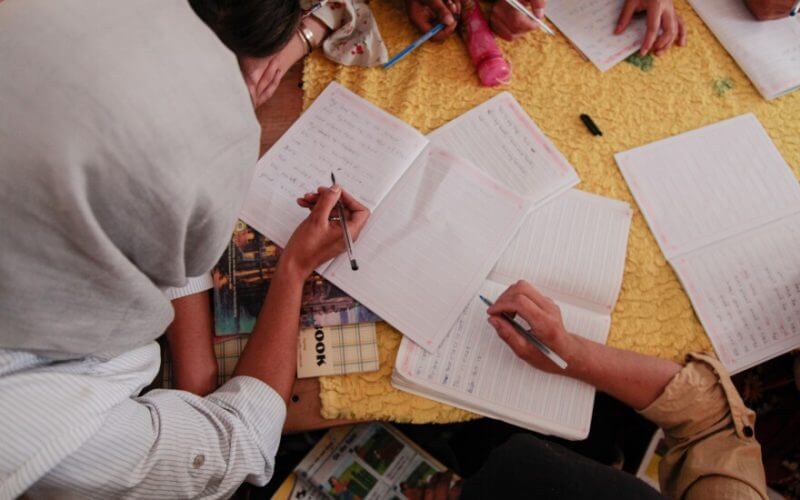

Inside a small room in a house on Kabul's outskirts, about ten teenage girls are defying their Taliban rulers who have banned them from attending secondary school. "Let's learn," one student slowly reads to another as they review English lessons from a textbook. "Learn the words: Yellow, blue, red, green."

The girls attend a secret school run by a young woman barely older than her students, 21-year-old Nazanin, whose lavender headscarf matched her nail polish on the day we visited.

"When the Taliban said girls can't go to secondary school anymore, I thought to myself, 'what can I do?'," she tells NPR. "How can I raise the morale of the girls around me?" She and the young students requested they only be referred to by their first names, to avoid being identified by Taliban officials.

It's been nearly a year since the Taliban seized power and stopped some 850,000 Afghan girls from attending secondary school, according to UNICEF figures. The regime had promised to allow girls to return on March 23. But it appears a minority of senior hardliners had a change of heart. Teenage girls arrived to their old classrooms only to be sent home again, many in tears.

The Taliban have been pressured to reverse their decision by the international community, Afghan women, girls — even prominent Afghan clerics known for their loyalty to the Taliban. An Education Ministry spokesman tells NPR they're ready to open those schools whenever their leadership says they can. But hopes are slim. At a nationwide conference of Taliban loyalist clerics and traders that took place from June 30 to July 2, local media reported that girls education was only mentioned by two of the 3,000 male attendees. The communique issued at the gathering's end called on the international community to recognize the Taliban administration but contained only a vague reference to education.

Many Afghan girls aren't waiting for the Taliban government to change their minds. Nor are their teachers.

In Kabul, the rural province of Parwan and the western city of Herat alike, women are running secret schools like Nazanin's. They're also finding loopholes around the Taliban's ban on girls attending secondary education, by operating girls madrassas — religious schools — or tutoring centers that essentially replicate high school courses.

"The fact that people have found all of these different ways to try to work around the Taliban ban is an indication of how desperately people want education for themselves, for their daughters, for the for the girls in their families," says Heather Barr, who for Human Rights Watch closely tracks violations against women and girls in Afghanistan.

While some governments may let poor girls fall through the cracks of the school system or have educational or general policies that discriminate against girls, only Afghanistan has banned girls' secondary education outright, she says. "The Taliban should be deeply ashamed that they've made Afghanistan the only country in the world that's denying girls access to education based on their gender."

After the Taliban reneged on their promise to let girls return to secondary school in late March, Nazanin decided to open her small school. Those close to her pitched in. She described her thinking at the time: "If we follow the Taliban, we'd just stay home. No. We have to do something."

Her family helped transform a spare room in their house and painted it a warm yellow. Her grandmother donated a rug. Friends handed over books. Nazanin teaches grades seven and eight as well as art. Her cousin teaches the older grades. A friend handles the English class.

Word of mouth has filtered across the alleyways in Nazanin's hardscrabble, working-class area. Her class is filled with students like 14-year-old Leila.

Leila pulls out a black pen from her Barbie-themed pencil case, opens her notebook and hunches over the low table she shares with the other girls. She copies English sentences off the whiteboard. "She is pretty," she whispers as she writes. "Our classroom is hot."

The Taliban's ban is just the latest barrier to Leila's education. During the pandemic, Leila missed a year of schooling. Last year, after she returned, tragedy struck: militants targeted teenage girls at her school, Sayed al-Shuhada, as they were streaming out of the gate, detonating a vehicle rigged with explosives that killed more than 80.

Leila was still inside her school when the attack occurred, but she lost many of her friends. And yet she returned three days later, expecting to resume studies. The school hadn't even reopened. Weeks later, her parents pulled her out, fearing another attack. Then, the Taliban swept to power.

Now, Leila walks to her secret school from her house nearby.

To avoid suspicion, she tucks her notebooks behind whatever novel she's borrowed from Nazanin's modest book collection. This week, it's a book of Persian poetry. The girls think if they're seen reading, that's okay. But studying — that could get them into trouble.

The Taliban, as a group, don't all agree on banning girls' secondary education. One senior Taliban bureaucrat requested anonymity to explain the ban to NPR because of the subject's sensitivity. He says the Taliban's hardcore loyalists demanded the ban in accordance with the conservative tradition that girls should stay home.

There are exceptions: The ban isn't applied in a handful of provinces where community leaders, typically men, voice support for girls' education.

The ban, paradoxically enough, does not apply to colleges either.

That has led to a surreal situation in Afghanistan where teenage girls must stay home, but a young woman lucky enough to have been in college when the Taliban seized power can still legally pursue her degree. A lack of professors to teach the women alongside strict dress codes appears to have kept many college-age women home, however.

The Taliban official says that in places where the ban is in effect, girls and their families can pay to attend privately run tutoring centers, where students typically go to improve their grades.

It's not clear how many Afghan girls are in secret schools or otherwise finding ways to educate themselves, but it almost certain that it is only a fraction of the some 850,000 girls who live in parts of Afghanistan where secondary schools have closed. According to UNICEF figures from 2019, which was the last time a school census was conducted, there were 1.1 million girls in secondary school. Some 250,000 of those girls live in provinces where secondary schools are still operational.

In Kabul, some of the luckiest girls end up in a basement on a quiet Kabul street, where 34-year-old Zainab set up a tutoring center in April to keep girls learning. She conducts online language lessons for Afghans abroad to raise money and is seeking external sponsors as well. "We cover secondary school subjects. We even hired teachers who lost their jobs. It's all free. I don't [want] the girls to miss out on an education."

Zainab says Taliban authorities have informally allowed her to run the center, provided the girls obey strict dress codes. And they do: The teenagers filter in wearing black robes, headscarves and face masks.

The center offers classes for English and Quran memorization. The most popular course prepares girls for the college admissions test. It's unclear, however, if the Taliban will allow new female college entrants.

One top achieving student at Zainab's center, 17-year-old Sahar, says her current situation is not like school.

She's meant to be in grade 11. She goes to three different tutoring centers to round out her education. She leaves home at 6 a.m. each morning and races between classes. She worries her bag, filled with books, might attract hostility. "I get really scared when the Taliban guys see me. I change my routes," she says.

Some days, Sahar says, her morale collapses. "I've always wanted to be a doctor and until the Taliban took over, I was getting top marks. Now I've got no chance. She and her mother cry together sometimes, Sahar says, "because our future is so dark."

It's a deep sadness she says her mother shares. Because when the Taliban were last in power, her mother was a teenager. And she couldn't attend school either.